Four million new homes will be needed in the UK by 2040, according to Cushman & Wakefield, the real estate consultants. Not everyone would be able to afford, or would want to buy one, so many more will be renting. As a result, the Private Rented Sector’s (PRS) share of all UK homes is expected to rise from 20% to 25%. To support this, rented supply needs to increase by 43%. Where will additional capacity come from?

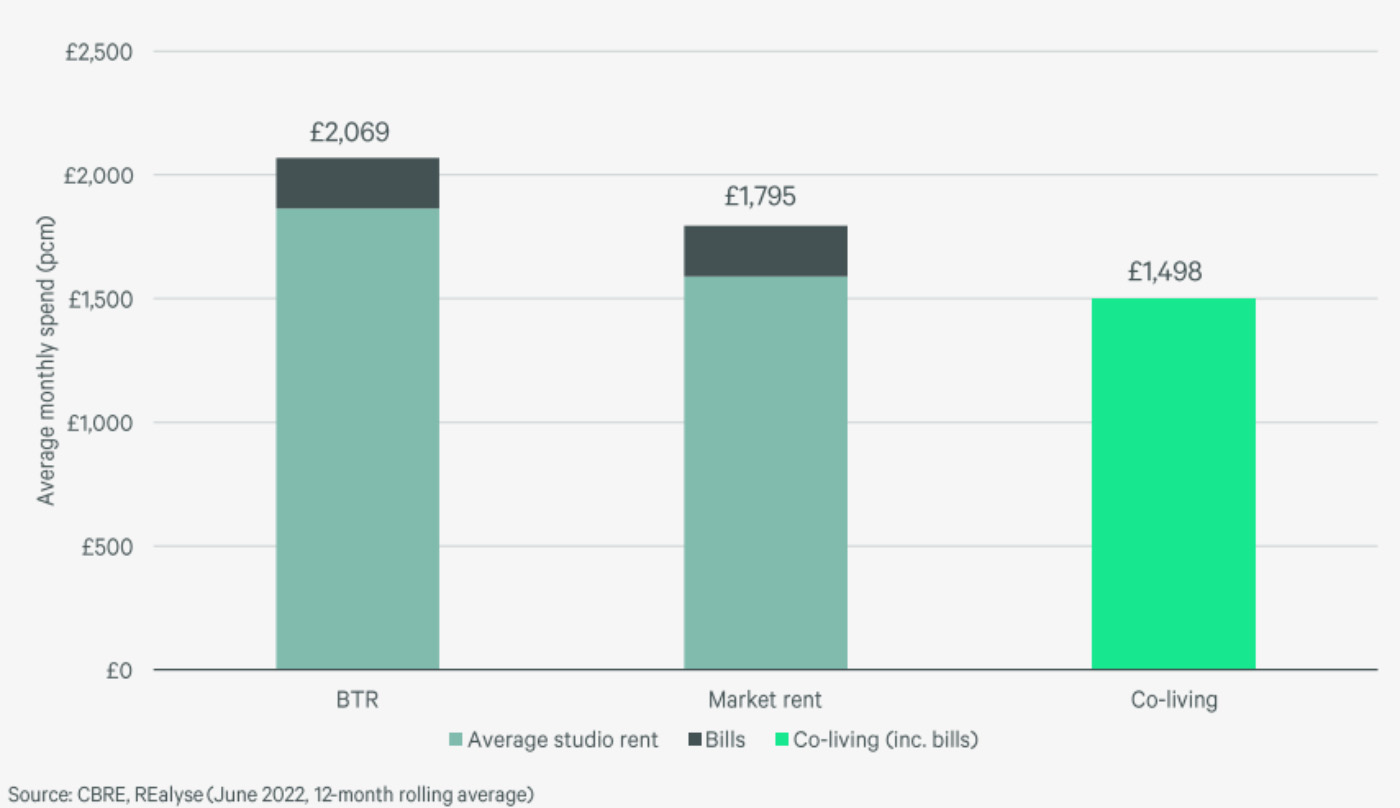

Cue flexible housing known as Co-living. The umbrella term includes the Co-living segment itself but also Build to Rent (BTR), and Student accommodation (PBSA). PBSA is housing specifically designed for students and addresses the lack of quality student accommodation in large cities. Co-living is designed for individuals who wish to rent rooms or studios in shared spaces. They are popular with young professionals and digital nomads who seek affordable housing in trendy urban locations. BTR are residential complexes designated for rent rather than sales. They include amenities such as gyms, swimming pools, gardens, and co-working spaces. The BTR demographic is somewhat older and includes young families. Co-living, due to its size, is more affordable than BTR and is usually cheaper than traditional PRS in large cities.

Each of these alternative living segments is designed to cater to a distinct demographic, but many have common features such as the emphasis on community and experience, sustainability-centred construction, and good transport links.

Comparison of tenant spend, London (Cushman & Wakefield)

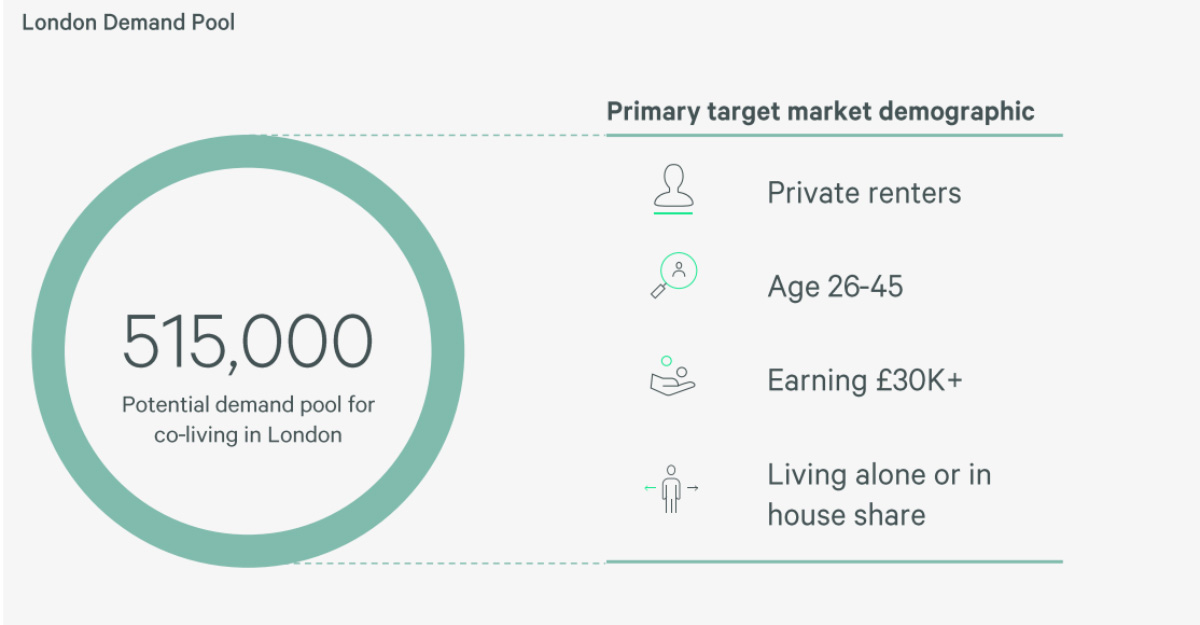

Co-living developments have sprung up in cities from Berlin to New York with a focus on the younger generation who prioritise community and flexibility: rent periods start from 3 months and residents have access to coworking spaces enabling them to work from home.

Projections for addressable market for Co-living in London (Cushman and Wakefield, 2022)

What are the advantages of Co-living for developers?

Co-living projects are subject to different regulatory requirements compared to traditional housing. London’s GLA introduced H16 policy within its Shared Living Guidance (LPG) document that regulates acceptable standards for such developments in the capital.

- Minimum Living Space. Living spaces should be adequately sized (typically 18-30 square metres) and should include a private bathroom and a kitchenette. Nevertheless, Co-living spaces do not need to strictly adhere to minimum internal space standards for new dwellings, provided they can offer high-quality shared amenities: kitchens, lounges and workspaces.

- Minimum rental periods: Some of the Co-living categories have leases called ‘memberships’ that fall outside of Assured Shorthold Tenancy (ACT) agreements. They are structured as license agreements that offer less security to tenants but might be preferable to people looking for short-term living solutions (serviced-apartment model). The other class of Co-living, ‘Suis Generis’, is AST-assured and is more long-term focused. Most of the new ground-up developments are Suis Generis, whereas many of the C1 class properties have been redeveloped from existing dwellings.

- Not suitable for families: Co-living spaces generally focus on single-occupancy units. The new generation of Co-living developments come with ‘Twodios’, where two people live in a 2-bedroom unit with a shared kitchenette.

- Affordability: The H16 policy states that Co-living spaces should be more affordable than standard market rent once all the bills are included. In London this generally means a 15%-30% ‘discount’ depending on location. Given their business model Co-living developments usually do not offer Affordable Housing to tenants, instead opting for cash-in-lieu contributions to the council, who then can provide Affordable Housing units off-site.

According to Savills, there were 25,021 Co-living beds in the UK in 2023. London leads the way, but there is a growing pipeline in Manchester, Birmingham, Glasgow and Sheffield (1). Some of the key players in London are Re:Shape, Folk (Sunday Mills, Palm House, and Florence Dock), The Collective (Canary Wharf and Old Oak Common), Mason + Fifth (Italian Building), Ark (Wembley Ark) and Node (Brixton). Most of the recent developments have shown strong take up rates, whereby 300+ newly installed beds have been leased up within a 3-month period. Thus, underscoring existing demand for the product.

Institutional demand:

In their annual survey in 2023, Savills identified £2.6bn of institutional money targeting the UK Co-living segment in the next 3 years. One recent example is Swiss Life Asset Management partnering with True North Real Estate to fund further purpose-built developments in Central London. The trend of JVs between institutional and family office money is likely to rise as investors become more comfortable with the sector. There are also several REITS that have been launched targeting the alternative living segment.

Conclusion:

The rise of Co-living has not been without its issues. The Covid pandemic has affected many early developments some of which needed to be restructured. Municipal authorities have had different responses to purpose-built developments, although the planning criteria have been streamlined with the introduction of major policy documents such as London’s LPG. The sheer need for housing in major economies has been a tailwind for the sector. Co-living housing offers desirable locations at cheaper prices for young professionals who embrace experience and community living. They also address some of the pressing issues facing young people today: the feeling of loneliness and the want of flexible working. As more councils give approval to new schemes in densely populated cities and developers gain expertise in the nascent sector, institutional money is likely to continue putting money to work. The next article in the series will put a spotlight on the BTR and the PBSA segments of the flexible living market.

Note: (1) ‘UK Co-living 2023’, Savills annual report on Co-living sector